Funeral Arrangements and Customs

Many of the Jewish Customs and rituals of a funeral are not known or understood by most people. At Kehila Chapels, all religious requirements regardless of one’s level of observance are respected. Our directors and staff are able to explain the various guidelines followed by Jewish families. Although morning is a very personal experience, please keep in mind that there are many varying mourning customs and one should always try to follow one’s family’s or community’s practices.

We suggest that you always consult with your Rabbi for personal guidance and to answer your questions related to Jewish funeral and mourning traditions. If you do not have access to a personal Rabbi, please feel free to contact Kehila Chapels. We will refer you to a Rabbi sensitive to your family’s special needs and who will try to answer your questions and advise you.

Avelus

Aninus is immediately followed by Avelus (mourning). Avelim (mourners) avoid music and concerts. They do not attend any joyous events or parties such as marriages or Bar or Bat Mitzvahs, unless absolutely necessary. They should consult a Rabbi for specific guidelines.

Avelus consists of three distinct periods:

Immediately after the funeral, the mourner begins Shiva (literally translated from Hebrew to mean “seven”). The day of burial is counted as the first day and the seventh day usually concludes after the Morning Prayer services.

Upon returning from the cemetery the mourners partake of a special meal traditionally provided by family, neighbors, or friends of the bereaved. Also, at this point in bereavement, friends move from the role of a spectator to a participant in the relief of the mourner’s anguish. Mourners should be served bread or rolls considered to be the staff of life and hard-boiled eggs symbolic of the circle of life.

Eggs are also the only food which hardens when cooked, teaching us that man must learn to steel himself when death occurs. This meal should be the first one eaten on the day of internment.

It is a tradition to cover all mirrors in the Shiva home except in bathrooms. This is done because self-adoration and one’s concern with the external appeal should be minimized because of the personal family tragedy.

For a more detailed explanation of shiva, etiquette for one visiting a shiva house, as well as a shiva calendar, we suggest you review the complimentary booklet: The First Seven Days by Meir Wikler

The thirty-day period following the death (including the Shiva) is known as Shloshim, (literally translated from Hebrew to mean “thirty”). During Shloshim, a mourner is forbidden to marry or to attend a Seudas Mitzvah (“religious festive meal”). Traditional men do not shave or get haircuts during this time.

Those mourning a parent additionally observe a twelve-month period counted from the day of death. During this period, most daily activities return to normal. The mourners continue to recite the mourner’s Kaddish as part of synagogue services for eleven months, rather than twelve, yet there remain restrictions on attending festive occasions and large gatherings, especially where live music is played until after the twelfth month.

The central theme of the Kaddish is the magnification and sanctification of G-d’s name. In the liturgy, different versions of the Kaddish are used functionally as separators between various sections of the service. The term “Kaddish” is often used to refer specifically to “The Mourners’ Kaddish“, said by mourners in all prayer services as well as at funerals and memorials. When mention is made of “saying Kaddish“, this unambiguously denotes the rituals of mourning.

If a family is unable to assume the responsibility of the kaddish three times each day for their loved one, please contact us for assistance.

Monuments

Jewish Tradition prescribes the placement of a matzeiva (monument) on the grave of a loved one not only as a sign of love and respect but as part of the mitzvah of honoring the memory of the deceased and to mark the location of the burial forever. The selection of a personalized monument or its inscription becomes an opportunity to perpetuate specific memories and establish a unique tribute.

For information regarding selecting, inscribing, and arranging for an appropriate monument please visit Kehila Monuments

The Unveiling

It is a religious obligation to place a marker at the grave of a loved one; an unveiling (Hakamas Hamatzeivah) is a graveside religious ceremony marking the formal setting of a loved one’s monument at the cemetery. According to Jewish custom, the monument may be set any time at or after the Shiva. Most American Jews hold the unveiling service close to the end of the year of mourning. Custom dictates a brief ceremony, with family and friends present.

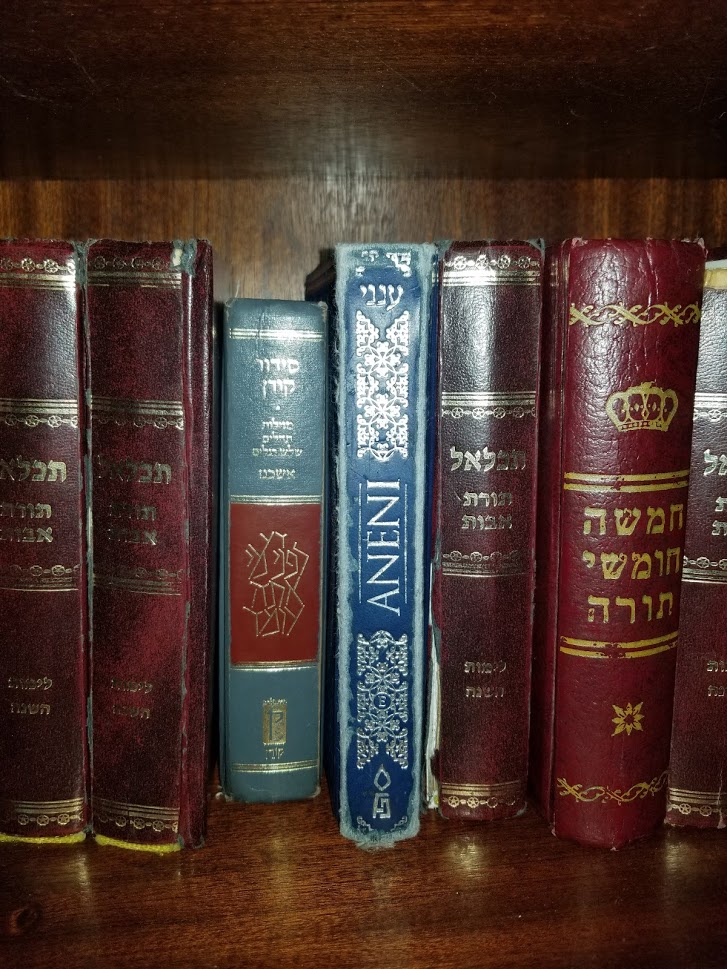

Generally, at the gravesite before the unveiling Psalms 33, 16, 17, 72, 91, 104, 130, and 119 are traditionally recited. This is followed by some brief words about the deceased, the actual unveiling of the stone, the Kel Maleh Rachamim (the Memorial Prayer), and the Kaddish.

If you do not have access to a Rabbi, please feel free to contact Kehila Chapels. We will refer you to a Rabbi that will meet your family’s special needs and who will try to answer your questions and advise you.